The guards led him. That was their function. Their hands were firm on his arms, but not rough. It was the kind of grip you use on a piece of equipment that needs to be moved from one place to another. Elias Vance was no longer a person. He was a problem being relocated for processing. They walked down corridors that were no longer his home, but just the sterile, curving tubes of a machine he had tried to understand. The machine was now showing him how it worked.

They arrived at the Synod Chamber. The door slid open with a soft hiss, a sound that swallowed itself. The chamber was a perfect circle of seamless, non-reflective grey. It was an anechoic room, designed to absorb all sound, so that the only thing you could hear clearly was the voice of authority. Fourteen seats for the Synod Assembly were arranged in a ring. Fourteen men sat in them, their faces as smooth and placid as stones in a river. Their Cognitive Anchors were working perfectly.

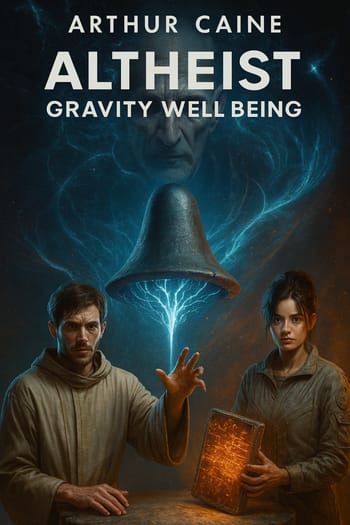

Abbot Clement stood on a low, circular dais at the center. He was not wearing his simple habit. He wore a more formal tunic, the same off-white, but with a broader red stripe on the sleeve. It was a robe for a judge. He looked at Elias, and his cold blue eyes held no anger. They held a kind of weary finality, the look of a man who has to perform a necessary, unpleasant task, like putting down a sick animal. This was not a trial. It was a procedure.

— Brother Elias Vance, — Clement said. His voice was the only thing in the room with any texture. It was calm and measured, each word a carefully placed stone. — You stand accused of sowing discord, of violating the Doctrine of Gentle Obscurity, and of consorting with the demon of lonely truths.

Elias said nothing. His objective was simple: to breathe. To stand. To not give them the satisfaction of his collapse. The obstacle was the crushing weight of the room, the fourteen pairs of empty eyes, the Abbot’s perfect, unshakeable certainty.

Deacon Marcus stepped forward from beside the dais. He held a familiar object in his hands. It was the Cracked Slate of Korbin. It looked different here, under the chamber’s shadowless light. It no longer looked like a key. It looked like a piece of broken junk, a shard of something dirty. The web of fractures across its screen seemed like a diagram of a disease.

— We present this artifact, — Marcus said, his voice full of a practiced, paternal sorrow. — Found in the heretic’s possession. It is a vessel for the raw, un-shepherded Sum. A direct conduit for the psychic infection he sought to spread among us.

He placed the slate on the dais before Clement. The symbol of his entire rebellion, the one tangible piece of a dead man’s hope, was now Exhibit A in his own damnation. The value axis of his world, which had tilted so painfully toward a meaning he could author himself, was now being forced back down by the sheer gravity of their faith. The move was a physical sickness in his gut.

Clement looked down at the slate. He did not touch it.

— The pursuit of truth without the guidance of faith is not wisdom, — the Abbot said to the assembly, but his eyes were on Elias. — It is pride. It is a sickness of the self. This sickness cannot be allowed to spread. It must be cleansed.

He reached down and picked up the Cracked Slate. He held it up for the fourteen silent men to see, a priest displaying a cursed relic. Elias watched the light catch on the fractured screen. He remembered Lena’s fingers tracing those same cracks in the quiet of her workshop. He remembered the thrill of seeing Korbin’s words appear. It felt like a memory from another man’s life.

— We do not burn our heretics, — Clement said softly. — We show them mercy. We cleanse the vessel.

With a single, economical movement, he brought the slate down against the hard edge of the dais.

The sound was sharp and final. A crack, like a bone breaking. The slate, already weakened, shattered into a dozen pieces. They skittered across the polished floor, dark and useless. The light in its screen died. The symbol was gone. The hope it represented was reduced to trash on the floor. It was a symbolic loss, the whiff of death for the entire idea that there was a truth outside of the one they manufactured. Elias felt something inside him break with it. The price of his rebellion was not just his freedom. It was the very idea that he had ever been right.

Clement brushed a shard of the casing from his hand. He looked at Elias, his expression unchanged.

— The vessel is cleansed, — he said. — Now for the soul.

He folded his hands. The trial was over. The verdict had been written before Elias had even entered the room.

— Elias Vance, for your crimes against the peace and stability of the Penrose Oratory, for your embrace of the chaotic void, you are sentenced to the Anamnesis Maze.

A few of the assembly members blinked. It was the only reaction. The Anamnesis Maze was not a place. It was a condition. It was the sentence given to the senior monk Elias had seen in the Choir. Permanent, unmediated connection. Psychic erasure. A fate worse than death, because the body was left behind as a monument to the failure of the mind.

Clement gave a small, almost imperceptible smile. It was not a smile of triumph. It was a smile of perfect, logical closure.

— You crave the raw truth, — the Abbot said, his voice dropping to a near-whisper that filled the silent room. — You shall have it. All of it.

The guards took his arms again. Their grip was the same. Firm. Impersonal. They turned him and began to lead him from the chamber. He did not resist. There was nothing left to resist with. He had lost his ally, his tools, his evidence, and now, he was about to lose himself. He was a ghost being led to his own haunting.

The anechoic walls of the Synod Chamber drank the sound of their footsteps. The air outside felt thick and heavy, full of the station’s low, placid hum.

He was being taken to the Choir. His mind was about to be erased.