The church was a skeleton. Ribs of stone clawed at a sky the color of dirty steel. What was left of the roof had collapsed inward, a jumble of shattered timbers and tiles piled on the nave floor. Snow dusted the wreckage, a thin white sheet over the bones of a dead god. It was cold, a deep, penetrating cold that settled in the marrow. They found shelter in the crypt, a small, vaulted space beneath the main altar that smelled of damp earth and frost. It was not safety. It was a pause.

Kulagin, the Sergeant Major whose loyalty was a physical presence, checked the single entrance, his submachine gun held ready. Zoya, the partisan, had found a corner away from the others. She sat sharpening one of her knives on a loose piece of stone, the rhythmic scrape-scrape a small, persistent sound in the heavy silence. Morozov, the political officer, was an empty uniform propped against a wall. His eyes were open but saw nothing. He was a broken thing, a casualty of a war he had only ever observed. Sineus watched them, the pieces of his broken command. His head throbbed with a dull, familiar ache, the ghost of the station’s chaos.

Sokolov, the scientist, moved through the small space with a restless energy. He was not a soldier. He was a man of books and laboratories, and the raw physicality of their flight had worn him down to wire and bone. He stopped at the remains of a baptismal font, a heavy stone basin cracked down the middle. The basin was dry, filled with dust and rubble. Sokolov reached in and picked up a single, smooth stone, no bigger than his thumb.

He walked over to Sineus. He held out the stone.

— Take it, Commander.

Sineus looked at the scientist, then at the stone. He did not move.

— Why?

— An experiment. Please.

Sineus took the stone. It was surprisingly heavy. He closed his hand around it. Sokolov watched him, his eyes intense, analytical.

— What do you feel?

The question was absurd.

— I feel a rock. It’s cold.

— No, — Sokolov said, his voice quiet but insistent. — Close your eyes. Concentrate. What do you feel?

Sineus wanted to throw the stone against the wall. He wanted to tell the scientist that they were being hunted, that they had no time for games. But he saw the exhaustion in Sokolov’s face, the desperate sincerity. He had paid for this man’s life with his honor, with Kulagin’s life. The price was already paid. He might as well see what he had bought. He closed his eyes. He focused on the object in his hand.

It was cold. And it was smooth. Unnaturally smooth. The surface felt like it had been polished by a thousand years of running water. He could feel the current against his skin, the gentle, persistent pull of a riverbed. He could smell the clean, metallic scent of fresh water and wet moss. The throbbing in his head sharpened for a moment, a spike of pressure behind his eyes.

He opened his eyes. The crypt was silent. The smell of damp plaster returned.

— It’s cool, — Sineus said, his voice rough. — And smooth. Like it came from a river.

Sokolov gave a thin, tired smile. It was not a smile of victory. It was a smile of confirmation.

— This church is a hundred kilometers from the nearest major river. That font has been dry for fifty years. The stone has never been wet in your lifetime.

Sineus looked down at the stone in his palm. It was just a piece of grey rock. The feeling of water was gone.

— What is this? Some kind of trick?

— It is memory, — Sokolov said. He took a step closer. — Not your memory. The stone’s. It was part of a riverbed for centuries. It remembers. Reality is not a fact, Commander. It is a story, written and rewritten. And memories are the words. Most people need artifacts to read them. You do not.

The headache flared again. Sineus felt a wave of revulsion. This was the world he had tried to escape. The world of his ancestors, with their talk of visions and bloodlines and destiny. The world of the charlatans and the mad monks who had clung to his family like leeches. He had chosen the Red Army for its brutal, simple truth. Steel and blood and orders. This was a poison.

— I am a soldier of the Soviet Union, — Sineus said, his voice flat and hard. — Nothing more.

— You are a Sensitive, — Sokolov corrected him, his tone clinical. — A person with the innate ability to perceive and interact with memory. It is why you get the headaches. It is the pressure of the world’s memory bleeding into your mind without a filter. It is why General Volkov chose you for this mission. He knew what you were. He was going to use you until your brain burned out, and then he was going to discard the husk.

Sineus stared at him. The words hit him like physical blows. Volkov’s parting words. Your instincts are why you were chosen. It had not been a compliment. It had been a diagnosis. He had been selected not for his loyalty, but for a flaw in his blood. A genetic curse.

— I don’t want it.

— It is not a choice! — Sokolov’s voice was suddenly sharp, cutting through his exhaustion. — Do you think you can simply will it away? That pressure you feel? It will grow. The Whispering Plague, the void left by all the memories Volkov and his kind have cut away, it is getting stronger. For a Sensitive, it is like the pressure before a storm. It will either drive you mad or it will kill you.

Sokolov’s breath plumed in the cold air. He was trembling, but his eyes were steady.

— I can teach you to build a shield. A mental technique to filter the noise. To control the input. It is your only chance of survival. It is our only chance.

Sineus looked from Sokolov to Kulagin’s empty space by the entrance. He looked at Zoya, a feral animal cornered and ready to bite. He looked at Morozov, a man whose mind had been erased by an idea. He was responsible for them. A debt is a debt. The hard right.

He hated it. He hated the weakness, the abnormality. But Sokolov was right. It was not a choice. It was a tool. A weapon. And he was a soldier. A soldier uses the weapons he is given. The cost was his own self-deception, the lie that he was just a simple commander. That lie was already dead.

— What do I have to do? — Sineus asked. The words tasted like ash.

Relief washed over Sokolov’s face, so profound it seemed to drain the last of his strength. He sagged against a stone sarcophagus.

— It is simple in principle. Difficult in practice. You must anchor your mind to something real. Something with a strong, simple memory of its own. Something you know. Your mind is a fortress. The sensory bleed is an ocean. You need to find the rock that is not the ocean.

Sineus looked around the crypt. The stones were too old, saturated with a thousand years of prayer and death. His uniform was just wool. His boots, just leather. His eyes fell to the pistol holstered at his hip. A standard issue Tokarev. He had carried it for three years. He had cleaned it a thousand times.

He drew the pistol. The metal was cold in his hand. He did not point it at anything. He simply held it.

— Focus on it, — Sokolov whispered. — Not the idea of it. The thing itself. Its weight. The texture of the grip. The memory of its purpose.

Sineus closed his eyes. He felt the familiar weight of the weapon. He felt the worn cross-hatching on the wooden grip, smooth in some places, sharp in others. He smelled the faint, clean scent of gun oil. He remembered the solid, mechanical click of the slide. The sharp crack of it firing. The simple, brutal physics of it. A spring, a hammer, a bullet. Action and reaction. It had no history but the one he had given it. It remembered only his hand.

Slowly, almost imperceptibly, the background noise in his head began to recede. The constant, low-grade pressure, the hum of a million distant, screaming memories, lessened. It was like sinking into a quiet room after hours in a loud factory. The throbbing behind his eyes eased, leaving only a profound weariness. For the first time in days, his mind felt like his own.

He opened his eyes. The crypt was the same. The air was still cold. But the world seemed sharper, the edges more defined.

Sokolov was watching him, a flicker of something like pride in his eyes.

— You see? It is a muscle. You must learn to use it.

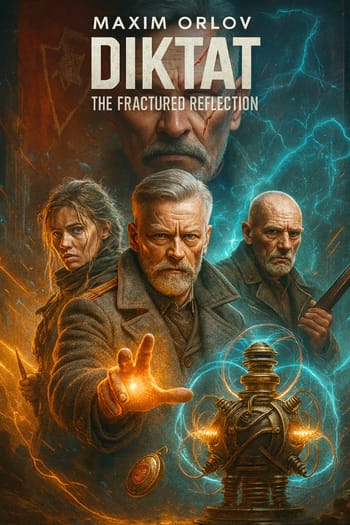

Sineus looked past the scientist. A piece of stained glass, deep blue and fractured, lay in the rubble near the font. It caught the weak light from the entrance. He saw his reflection in it. It was still broken, a face split by a dozen lines of dark lead. But the pieces were aligned. The image was clearer now. More solid. A man he was beginning to recognize.

He looked back at Sokolov. The man was no longer just a defector, a package to be protected. He was a teacher. A guide. A new and terrible responsibility.

The silence of the crypt was deep and absolute. The only sound was the faint whisper of snow against the stones above.