The rain was a constant, cold drum against the tavern’s grimy windows. It had been falling for two days, washing the filth of the shanty town into the churning, grey water of the Black Sea. Inside, the air was thick with the smell of cheap, sour wine, wet wool, and the acrid smoke of hand-rolled cigarettes. It was a place for men with no future and too much past. A perfect place to disappear. Or to buy a new direction.

Zoya entered alone. She did not look at Sineus. She moved through the crowd of fishermen and deserters with a fluid grace that did not belong in this place of broken men. Her rifle was gone, left with Kulagin. She carried only her knives, hidden beneath a rough wool coat. She went to the bar, a long plank of dark, sticky wood, and ordered a glass of something that looked like muddy water. She took a sip. Then she gave a single, almost invisible nod toward a corner booth. Two days. The search was over.

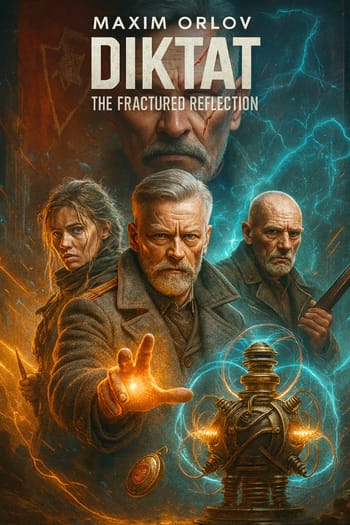

Sineus stood up. He left a few worthless coins on his own table. Kulagin, sitting ten meters away near the main door, shifted his weight. His hand never moved far from the submachine gun hidden under his long coat. Across the room, Sokolov, the scientist who was the cause of all this, looked up from a tattered newspaper, his eyes wide and nervous. He was a terrible actor. Zoya remained at the bar, a silent anchor, her back to the room but her attention fixed on the reflection in a dirty mirror. They were a machine with four working parts and one broken one. Morozov was still a ghost, a hollow shell they had to drag with them.

The corner booth was occupied by a single man. He was large, his shoulders straining the seams of a faded blue shirt. His hands, resting on the table, were thick with calluses and old, white scars. A wool cap was pulled low over his forehead. This was the man they called The Turk, the captain of a smuggling trawler named the Sea Wolf. He was their last chance.

Sineus slid into the booth opposite him. The Turk did not look up from his glass. He was watching the condensation trail down the side.

— I need passage, — Sineus said. No preamble. No negotiation. A statement of fact.

— The sea is full, — the man said without looking up. His voice was a low rumble, like stones grinding together.

— Passage to Istanbul, — Sineus clarified. He kept his voice even. — For five people.

The Turk finally raised his head. His eyes were dark and flat, the eyes of a man who had seen everything and was impressed by nothing. He had a thick, untrimmed grey beard, stained yellow with tobacco. He looked past Sineus, his gaze sweeping the room, noting Kulagin by the door, Sokolov pretending to read, Zoya at the bar. He was a professional. He understood the geometry of the room.

He laughed. It was not a pleasant sound.

— Istanbul. For five. You have a sense of humor, Commander. Or you are a fool.

— I am neither.

— The Black Sea is a graveyard, — The Turk said. He took a long drink from his glass. — The Germans hunt with planes by day. Your own people hunt with patrol boats by night. The mines wait for everyone. It is suicide. I do not sell suicide. It is bad for business.

Sineus reached into his coat. He placed a small, heavy leather bag on the table. It made a soft, clinking sound. The sound of gold. The Turk’s eyes flickered down to the bag. He did not move to touch it.

— I am not a ferryman for refugees. Gold does not stop a torpedo.

— This is not refugee gold, — Sineus said. — It is payment.

The Turk stared at him for a long moment. He was weighing the man, not the money. He finally reached out a thick finger and pushed the bag. It was heavier than it looked. He untied the leather thong and tipped a single gold coin into his palm. It was an old coin, from a dead empire. He bit it. The soft metal gave slightly under his teeth. He nodded to himself.

— It is good gold. But it is not enough. Not for five bodies. Not for a trip to the bottom of the sea.

Sineus watched him. He saw his own reflection in a pool of spilled wine on the dark wood of the table. The face was distorted, broken by the uneven surface. A stranger’s face. A beggar’s face. He thought of Kulagin’s locket, of the child’s drawing inside. The hard right.

He pushed the entire bag across the table.

— All of it.

It was everything they had left. The last remnant of his family’s name, melted down into anonymous, untraceable currency. He made the choice. He felt the cost of it in his gut, a cold, hollow space where his past used to be.

The Turk did not look at the bag. He looked at Sineus’s face. He saw the desperation, but he saw something else behind it. Something hard and unbending. He picked up the bag, weighing it in his palm. The gold was a heavy, solid fact. It was a powerful argument.

— For this, — The Turk said slowly, — I will try. But the risk is mine. The final decision is mine. If I see a patrol, I run. If I have to throw you to the fishes to save my ship, I will. Understood?

— Understood, — Sineus said.

The Turk nodded. He pushed the bag of gold into a deep pocket inside his coat. The deal was done. But he did not stand up. He leaned forward, his voice dropping lower.

— And one more thing.

Sineus waited. A debt is a debt. It must always be paid.

— Gold pays for the fuel. It pays my crew. It does not pay for my life. You will owe me a favor.

The word hung in the smoky air between them. A favor. An unknown price. A blank check written on their future, a future they might not even have. Sineus felt the weight of the new debt settle on him. It was colder and heavier than any gold.

— Agreed, — Sineus said. His voice was flat.

The Turk grunted, satisfied. He had won. He had taken the gold and a piece of the man. He stood up, his large frame blocking the light.

— My ship is the Sea Wolf. Be at the west dock at midnight. There is a pier with a broken lamp. Wait there. If you are late, I am gone.

He turned and walked away, disappearing into the crowd without a backward glance. The negotiation was over.

Sineus remained in the booth for a moment. He looked at a polished brass rail along the back of the seat. He saw his reflection again. It was still fractured by the curve of the metal, but the image was sharp and clear. The face of a man who had made a hard choice and now owned it. It was not a beggar’s face. It was his own.

He stood and walked back through the tavern. He gave a slight nod to Kulagin. He motioned to Sokolov. Zoya was already moving toward the door. They left the tavern and stepped out into the cold, clean rain.

The rain had washed the street clean. The air smelled of salt and wet stone.