The room was a box. Four grey walls, a concrete floor, a single steel door. In the center sat a plain wooden table and two chairs. There were no windows. The air was still and smelled of dust and cold metal. It was a room for taking a man apart, piece by piece. Pavel Morozov sat in one of the chairs, his back straight, his hands resting on his knees. He was unharmed. His uniform was dirty but intact. His mind was a fortress. Almost.

He had been waiting for three hours. The waiting was part of the process. It was a tool to soften the subject, to let his own thoughts become the enemy. Morozov knew the procedure. He had studied it. He had written reports on it. He was not the subject. He was a loyal officer of the Red Directorate. He repeated this to himself. A litany against the silence.

The lock on the steel door clicked. The sound was loud in the small room. The door swung inward. General Ivan Volkov entered. He was not wearing his greatcoat. His uniform was perfectly pressed. He did not look at Morozov. He moved to the table and placed a small, heavy stack of books on the polished wood surface. The sound was a flat, final thud.

Volkov pulled out the other chair and sat down. He was not an interrogator. He was a professor about to begin a lecture. He folded his large, clean hands on the table.

— Pavel Andreyevich, — Volkov said. His voice was calm, a deep and reasonable baritone. It was the voice that had convinced a committee to approve the Oscillator. — Do you know why you are here?

— I failed to prevent the commander’s treason, — Morozov said. The words were ash in his mouth. He had rehearsed them. An admission of failure was the first step toward correction. It was doctrine.

— No, — Volkov said simply. He looked at Morozov for the first time. His eyes were pale grey, like a winter sky. They held no anger. Only a mild, academic curiosity. — You are here because you are a true believer. And true belief is the most useful and the most dangerous commodity in this war.

Morozov’s own faith was his shield. He held to it.

— I am loyal to the Party. To the State. My actions at the consulate were to report a traitor and secure a state asset.

— I know, — Volkov said. He gestured to the books on the table. They were the foundational texts. The works of Marx, of Lenin, of Stalin. The holy scripture of the Revolution. Morozov had read them all a dozen times. He could quote entire chapters from memory. — Your loyalty is not in question. Your understanding is.

Volkov opened the top book. The spine cracked. The pages were worn, the paper soft. He turned to a marked passage.

— ‘The revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat is rule won and maintained by the use of violence by the proletariat against the bourgeoisie, rule that is unrestricted by any laws.’ Unrestricted, Pavel Andreyevich. Do you know what that means?

— It means the old laws do not apply. That the needs of the Revolution supersede the morality of the old world, — Morozov recited. It was a simple catechism.

— Precisely, — Volkov said. He closed the book. — The Revolution is not a single event. It is a process. A constant, ongoing act of creation. We did not simply tear down the Tsar’s world. We are building a new one. And building requires tools. It requires a clean foundation.

He leaned forward slightly. The movement was small, but it made the room shrink.

— The army fights a war of territory. A war of meters and kilometers. We fight a war of history. A war of memory. The Oscillator is not a weapon. It is the ultimate tool of the builder. It allows us to clear the foundation. To erase the flawed structures of the past—the decadent ideas, the incorrect histories, the sentimental weaknesses—and build the perfect Soviet future on a clean slate. It is the next logical act of the Revolution.

The logic was a steel blade. It slid between Morozov’s ribs, seeking his heart. He had seen the projections from the Sokolov Cipher. The screaming void. The Whispering Plague.

— But the cost… The doctrine is clear. The Party exists to protect the people. The Oscillator erases them. It is a contradiction.

— Is it? — Volkov asked. He opened another book. — ‘The transition from capitalism to communism represents an entire historical epoch.’ An epoch. Not a day. Not a year. Who are ‘the people,’ Pavel Andreyevich? The flawed, sentimental, backward-looking men and women of today? Or the perfected Soviet man of tomorrow? The one who will inherit the world we build for him?

Volkov’s voice was soft, hypnotic.

— We do not serve the people of the present. They are the raw material. The iron ore we must melt down to forge the steel of the future. We serve the future. We serve the children of that future. And to protect them, we must be unrestricted by the sentimental laws that protect the ore in its raw, impure state. We must be willing to burn away the dross.

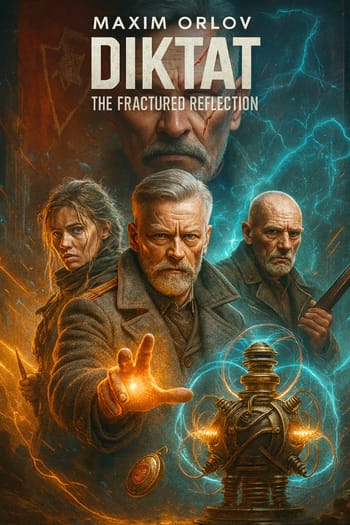

Morozov felt a crack form in the fortress of his mind. He looked down at the polished surface of the table. His own reflection looked back at him, pale and thin. For a second, the image wavered, splitting in two. A fractured, broken face, the pieces not quite aligned. He blinked, and the image was whole again. But the crack remained.

— Sineus does not understand this, — Volkov continued, his voice a low murmur. He had seen the flicker of doubt in Morozov’s eyes. He pressed his advantage. — He is a good soldier. A fine commander. But he is flawed. His noble blood makes him sentimental. He feels pity for the dross. He sees the hard right, as his sergeant would say, but he thinks it applies to individuals. He does not see the greater hard right, the one that requires us to sacrifice millions today to save billions tomorrow.

The General’s words were a solvent, dissolving the mortar of Morozov’s faith. He had seen Sineus’s weakness. He had reported it. He had tried to act on it.

— I saw his weakness, — Morozov said, his voice thin. — At the consulate. I tried to make contact. To do my duty.

Volkov smiled. It was a genuine smile this time, one of pride.

— Yes. You did. Your intent was pure. Absolutely correct. You saw the flaw in the tool, and you tried to alert the craftsman. For that, you should be commended.

The praise was a sudden warmth. Relief flooded through Morozov. He had been right. His faith was justified.

— Your methods, however, — Volkov added, and the warmth vanished, replaced by an arctic chill. — Were clumsy. Amateurish. You passed a note like a schoolboy. You were observed by the broker, by the Germans, by everyone. You compromised yourself and your contact for nothing. If I had been relying on you, Sineus would be in Cairo by now.

The words were not an accusation. They were a statement of fact. A dismissal. Morozov felt the blood drain from his face. He was not a loyal agent. He was a child playing a game he did not understand. His greatest act of faith had been a fool’s errand.

— I… I was following procedure, — he stammered.

— You were following the procedures of a dead war, — Volkov said, his voice flat. He leaned back in his chair. The lecture was over. — The war of paper and reports. This is a war of will. Of vision. Sineus has the wrong vision, but he has will. You have the right vision, but you have no will of your own. You only have the book. And the book is a map, Pavel Andreyevich, not a destination.

The fortress in Morozov’s mind did not just crack. It shattered. It collapsed into dust and ruin. The Party was not a shield. It was a furnace. The people were not its children. They were its fuel. Doctrine was not truth. It was a tool for men like Volkov. Men who saw the world as a thing to be unmade and remade in their own image.

He was nothing. A believer in a god that did not exist. A loyal soldier of a faith that was a lie. He had been so certain. So pure. And it was all for nothing. He had been a fool. The most useless thing of all. A true believer.

Volkov stood up. He gathered the books from the table, stacking them into a neat pile. He did not look at Morozov again. He was an experiment that had concluded. A tool that had broken.

— We will find a use for you, — the General said to the air. — The state is ever resourceful.

He walked to the door. He did not look back. The door opened, and he was gone. The lock clicked shut. The sound was final.

Morozov sat alone in the silence. He stared at the polished surface of the table. His reflection stared back. The face was gaunt, the eyes wide and empty. It was not his face. It was the face of a stranger. A ghost. A man who had seen the machinery of the world and been ground to dust in its gears.

The motes of dust danced in the still air, illuminated by the single bare bulb. The silence in the room was absolute, a heavy blanket that smothered thought.