The wind was a solid thing. It hammered the rock face and poured into the mouth of the cave, a physical presence of cold and noise. Sineus huddled in the darkness, his back pressed against the rough stone. The blizzard had erased the world. It had erased the ridge, the bodies of the hunters, the still form of Boris Kulagin. It had erased everything but the cold and the high, screaming hum from the valley below. The sound of the Oscillator at Kavkaz-4. The sound of the end.

He was alone. Zoya was wounded, captured. Sokolov, the broken scientist who held the world’s last, terrible truth, was in Volkov’s hands. Kulagin was dead. The thought was a flat, heavy stone in his gut. Not a spike of grief. Not a wave of rage. Just a dead weight. A fact. A commander’s arithmetic. One sergeant major subtracted from the rolls.

Hope was a currency he no longer possessed. The cold was a patient enemy, seeping through the layers of his greatcoat, into his bones. He could stay here. He could let the cold take him. A quiet, anonymous end. A fitting grave for a traitor who had failed. It was the easy thing.

His fingers, numb and clumsy, found the object in his pocket. The brass locket. Kulagin had pressed it into his hand. A final order. A final debt. He pulled it out. It was heavy. Solid. The metal was dented and scratched, a veteran of a dozen campaigns, just like the man who had carried it. It was still warm from his body.

He fumbled with the clasp, his frozen thumb slipping on the smooth metal. It took three tries before it clicked open. He held it up in the gloom, angling it to catch the faint, grey light from the cave’s entrance. He expected a photograph. A wife, perhaps. A sweetheart from a life before the war.

There was no photograph.

Inside, protected by the brass shell, was a small, folded piece of paper. A child’s drawing. It was rendered in crude, waxy crayon. A lopsided house with a crooked door. A bright yellow sun with stick-like rays, smiling in a blue sky. It was the simplest thing in the world. It was the only thing that mattered.

This was Kulagin’s past. The memory he carried. Not a woman’s face, but a child’s promise of a world with smiling suns and houses that did not burn. This was what the sergeant had died for. Not for the state. Not for the Party. Not for the abstract idea of a perfect future built on a mountain of skulls. For this. For a child’s drawing.

Sineus stared at the scrap of paper. The weight in his gut shifted. It was no longer the dead weight of defeat. It was the heavy, binding weight of a promise. A debt of blood. Kulagin had not died saving a Red Army commander. He had died saving the man who held his last memory.

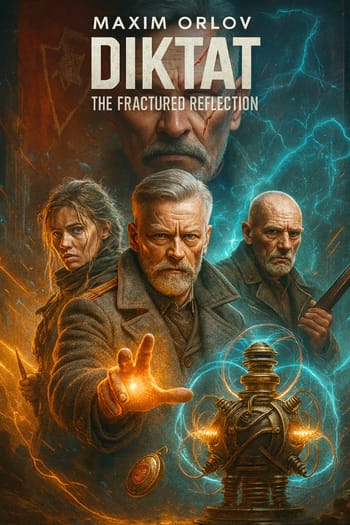

He looked at his own reflection in the polished inner surface of the locket. A face stared back, fractured by the dents in the brass. He saw the nobleman his father had raised, the boy who believed in honor. He saw the commander the Red Army had forged, the man who believed in duty. He saw the traitor Volkov had made, the man who had lied to his superiors. And he saw the Sensitive Sokolov had named, the man who felt the world screaming. The faces were all there, broken and overlapping. A shattered mirror.

But they were not fighting anymore. They were settling into place. The nobleman’s honor. The commander’s discipline. The traitor’s knowledge. The Sensitive’s power. They were not separate men. They were all him. He was not a tool of the state or a ghost of his bloodline. He was the man holding the locket. The choice was his. His alone.

The hard right is harder for a reason. Kulagin’s words. A simple truth for a simple soldier. Sineus finally understood. The hard right was not about dying for a flag. It was about choosing what you died for. He could surrender to the cold, a final act of loyalty to his own despair. Or he could walk back toward the screaming machine and fight for a child’s drawing of the sun.

His resolve settled, a cold, hard certainty that pushed the despair into a corner. It was a choice made without witness, in the absolute isolation of a frozen tomb. It was the only choice that mattered. He closed the locket, the click of the clasp loud in the silence.

He checked his gear. The inventory was short. Brutal. His Tokarev pistol. He worked the slide, the oiled metal a familiar comfort. He checked the magazine. Three bullets. He had a knife. That was all. The odds were not long. They were nonexistent. It did not matter. The arithmetic had changed.

Sineus stood up. His joints ached with the cold. He ignored it. He walked to the mouth of the cave and pushed his way out into the white fury of the blizzard. The wind tore at him, a physical blow. He leaned into it, a man walking into a hurricane. He put one foot in front of the other, his boots sinking into the deep snow. He was no longer running. He was heading back toward Kavkaz-4.

The snow was a curtain, visibility zero. He navigated by the sound of the Oscillator, the high, unholy scream a fixed point in the chaos. He moved for what felt like an hour, a ghost in a world of ghosts. Then he saw it. A dark shape against the white. Another rock outcropping, smaller than his own. A flicker of movement.

He approached, his pistol in his hand. He peered into the shallow overhang. Zoya was there. She was slumped against the rock, her face pale, her leg wrapped in a crude, blood-soaked bandage. She was alive. Her eyes, sharp and feral even in her exhaustion, found his. She held her knife in her good hand.

She was not beaten. She was waiting.

They were not a team. They were not a unit. They were two survivors at the end of the world. And they had one last, desperate option.

The wind howled, a long, mournful cry. The snow fell, burying the world in white.