The town was a ghost. It was a collection of grey, concrete-block buildings huddled against the cold, a place for rear-echelon clerks and quartermasters to wait out the war. The address Volkov had provided was for one of these anonymous apartment blocks. Number seventeen. A place meant to be invisible.

Zoya Koval moved toward it. She was the partisan guide assigned to them, a woman as quiet and grim as the winter landscape. She flowed through the deepening twilight, less a person walking than a shadow detaching itself from other shadows. She reached the door to the third-floor apartment and stopped. She did not knock. She produced a thin strip of metal from her pocket and went to work on the lock. There was no sound. Only a faint click as the tumblers gave way. She pushed the door open a few centimeters and froze, listening.

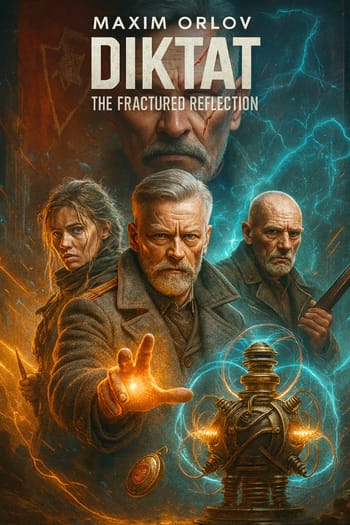

Sineus stood two meters behind her, his hand resting on the grip of his pistol. His goal was simple. Find Sokolov, or find a trail. Everything else was noise. Kulagin was a solid presence to his right. Morozov, the political officer, stood slightly apart, an observer by nature and by trade.

Zoya gave a slight nod. The apartment was silent.

Sineus moved past her, through the door. Weapon first. The air inside was stale, thick with the smell of cold tobacco and dust. It was a standard Directorate safe house. Functional furniture. A table, three chairs. A map of the region pinned to one wall.

Three men were in the room. All of them were dead.

They were Directorate agents, dressed in the same plain clothes as the clerks in the streets below. One sat at the table, a half-full glass of tea in front of him. Another was in an armchair, a book open on his lap. The third stood by the window, as if looking out at the street. There were no signs of violence. No overturned furniture. No blood. They looked like they had simply stopped.

Kulagin entered behind him, his submachine gun held low. He took in the scene with a single, sweeping glance. His eyes, accustomed to the brutal mathematics of the battlefield, searched for the cause. He found nothing. Morozov followed, his face pale in the dim light. He stopped just inside the doorway, his hand going to his mouth.

— Check them, — Sineus ordered, his voice low.

Kulagin moved to the man at the table. He was a professional. He checked for a pulse at the neck. Nothing. He lifted the man’s eyelid. The pupil was fixed and dilated. He sniffed the glass of tea. He shook his head. He moved to the second man, then the third. The process was the same. Efficient. Clinical.

— No marks, — Kulagin reported. His voice was a quiet rumble. — No wounds. No signs of a struggle. Their skin is cold. They have been dead for hours.

Morozov finally found his voice. It was thin, strained.

— It must be poison. A nerve agent. Something in the air. We should not be in here.

Sineus ignored him. He knew the smell of poison gas. He knew the look of a man choked out by chemicals. This was not that. This was something else. This was silence. This was absence.

He felt a familiar pressure begin to build behind his eyes. A dull throb that started small and grew, a tightening vise. It was the same headache from the rail junction. The same pressure from the Fracture. He fought against it, focusing on the room. On the details. The dust motes dancing in the weak light from the window. The way the pages of the dead man’s book were slightly curled from the damp.

He saw his own reflection in the grimy window pane. A tired, hard face staring back. For a second, the image doubled, a second face overlapping his own, its mouth open in a silent scream. A fractured reflection. He blinked, and it was gone.

— The windows are closed. The door was locked from the inside, — Kulagin said, his voice pulling Sineus back. — If it was gas, the killer would be dead, too.

— Sokolov is a scientist, — Morozov insisted, his need for a logical, state-approved explanation overriding the evidence. He wanted a report he could file. A box he could check. — He could have designed a poison with a delayed reaction. He could have an antidote.

Sineus walked deeper into the room, the pressure in his skull now a sharp, splitting pain. The air grew colder. He saw it near the center of the room. A place where the light seemed to bend wrong. It was a shimmering, vertical line, no wider than his hand. It looked like a flaw in glass, a heat haze that did not move. It buzzed, a low, insistent sound like a fly trapped behind a window.

A memory-wound.

The headache became a roar. The room dissolved. The sounds of his own men faded, replaced by the low buzz. He saw the room as it had been hours ago. The three Directorate agents were alive. They were talking. One was pouring tea.

Then he saw Sokolov.

The scientist was not there in body. It was an echo. A ghost of action impressed upon the world. Sokolov stood where the shimmering cut now hung in the air. He was calm. His movements were economical, precise. He was not a panicked academic. He was an operator.

In his hand, he held a blade. It was not steel. It was a piece of polished darkness, a sliver of obsidian that seemed to drink the light. It did not reflect. It only absorbed. A memory blade.

The echo of Sokolov made a single, precise cutting motion in the air. A motion like a surgeon making an incision. The buzz intensified for a second, then stopped.

The three agents stopped. The man pouring tea froze, his hand outstretched. The man reading the book stared blankly at the page. The man at the window went still. Their life, their momentum, their memory of being alive—it was all just… cut. Severed from them. They were not dead. They were erased.

The vision collapsed. Sineus was back in the room. The three dead men sat in their silent tableau. The shimmering wound in the air remained. Kulagin was looking at him, his expression concerned.

— Commander?

Sineus raised a hand, steadying himself against the table. The wood was cold. Real. He focused on the grain, on the solid fact of it, pushing the phantom images away. The debate was over. They were not hunting a simple traitor. They were hunting a man who could wield the fundamental forces of their world as a weapon. A man who could kill without leaving a mark.

— He was here, — Sineus said. His voice was rough. — He did this.

Morozov stared at him. — Did what? There is nothing here.

Sineus looked at the political officer. He saw a man willfully blind, a man whose entire existence was based on denying the truths that did not fit the doctrine. There was no point in explaining. You could not describe color to a man born without eyes.

The apartment door creaked. Zoya stood there. She had been outside, circling the building, reading the ground the way Kulagin read a battlefield.

— Trail, — she said. One word. It was all that was needed. — Heading west. Toward the marshes. It is fresh. Maybe four, five hours old.

Morozov stepped forward. — We must report this. We must secure the scene and wait for a full investigative team from the Directorate. That is proper procedure.

Sineus looked at the dead men. He looked at the shimmering wound in the air that only he could see. He looked at Zoya, waiting by the door. Proper procedure was a luxury. It was a tool for men who had time. Sokolov had a five-hour lead. By the time a team arrived from headquarters, he would be gone. The trail would be cold. The cipher would be lost.

He had to choose. The safety of the system, or the necessity of the hunt. The easy wrong, or the hard right. He thought of Kulagin’s words in the hospital. The choice was simple. He would trade the risk of the unknown for the certainty of failure. Abandoning procedure was the price. He paid it without a second thought.

— We move now, — Sineus said.

Morozov opened his mouth to object. — Commander, my duty requires me to insist—

— Your duty is to follow my orders, Political Officer, — Sineus cut him off, his voice cold steel. He turned to Kulagin. — Sergeant Major, strip the bodies of any documents. We take anything useful. We leave the rest.

Kulagin nodded, already moving. He understood. The hunt was still on. It had just become infinitely more dangerous. Zoya melted back into the hallway, ready to lead the way.

Sineus took one last look at the silent room. The dead men. The invisible wound hanging in the air. He was no longer a soldier following orders. He was a hunter on the trail of a monster, and he was five hours behind.

The wind picked up outside, rattling the window frame. It carried the smell of snow and damp earth.