The truck smelled of wet earth and diesel. Sineus drove. His hands were steady on the wheel, his knuckles white. The road was a pair of muddy ruts cutting through an endless, flat expanse of frozen farmland. Behind them, 150 kilometers of mud and forest separated them from the marsh. From the firefight. From the lie he had sent over the radio. It was not enough distance. It would never be enough.

His goal was simple. Keep moving east. Survival was the mission now. Everything else was secondary. He glanced at the fuel gauge. The needle was low. Another problem for later. There was always another problem.

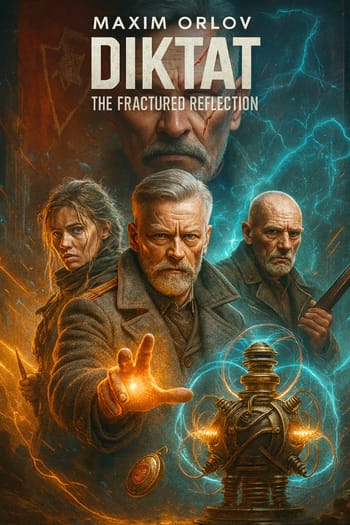

In the passenger seat, Sergeant Major Boris Kulagin was awake. He had been awake for two days. His submachine gun rested across his lap, its metal dark and oiled. He watched the horizon, his eyes missing nothing. Kulagin was a soldier. The world could end, and Kulagin would still be cleaning his weapon, watching his sector of fire.

The truck hit a pothole. The frame shuddered. In the back, a metal tin rattled. Zoya Koval did not look up. She sat cross-legged on a pile of damp sacks, drawing a whetstone along the edge of a long, thin knife. The sound was a quiet, rhythmic scrape. Shhhk. Shhhk. A predator’s lullaby. She had not spoken a word since they had stolen the truck from a deserted collective farm. She simply killed, and moved, and waited for the next chance to kill.

Beside her, Pavel Morozov stared at the canvas flap of the truck. His face was slack, his eyes empty. The political officer was a broken thing. His faith, the rigid iron spine of his entire existence, had been shattered by Sineus’s treason. He was a ghost in a Red Army uniform.

And then there was Sokolov. The scientist sat opposite Morozov, huddled in a threadbare coat. The man who had torn Sineus’s world apart with a few projected images and a single, damning phrase. Acceptable cost. Sokolov met Sineus’s eyes in the rearview mirror. There was no gratitude in his gaze. Only a cold, intellectual curiosity.

— You are a man of contradictions, Commander, — Sokolov said. His voice was thin, but it cut through the rumble of the engine.

Sineus’s jaw tightened. He kept his eyes on the road.

— Silence.

— You commit treason to save my life, to protect the truth I carry, — Sokolov continued, ignoring the order. — Yet you still wear the uniform of the men who would see the world burn. You still think like a commander. Who are you lying to? Them, or yourself?

— I said, silence, — Sineus repeated. The words were flat. Hard. An order.

Kulagin shifted in his seat. He did not look at Sineus. He did not look at Sokolov. He just watched the road ahead. Zoya’s knife stopped its rhythmic scraping. The sudden quiet from the back of the truck was louder than the engine.

Sokolov leaned forward.

— Your loyalty was a cage, Commander. You have opened the door. But you are still standing inside, afraid to step out. You think this is about survival. About escaping. You are still thinking on the scale of a soldier.

Sineus gripped the wheel. The man’s words were scalpels, cutting away the scar tissue of his old life. He was right. That was the worst part. He was right.

— What do you want, Doctor? — Sineus asked, his voice low.

— I want you to understand the weapon you are, — Sokolov said. — Volkov did. He chose you because you are a sensitive. He was going to use you, burn you out, and discard the husk. Your headaches, your… instincts. That is the world screaming at you. It is the Plague. You feel its pressure. You can see the echoes it leaves behind.

The memory of the shimmering shell over the rail junction. The phantom tanks in the sky. The fractured face in the shard of glass. It was not shell-shock. It was a sense. A terrible, unwanted sense. The strain of it was a constant pressure behind his eyes.

— You can learn to control it, — Sokolov pressed. — To shield yourself. To see clearly. Without the goggles and blades the Directorate and the Ahnenerbe rely on. You are the next step in this war. The only thing that can truly fight them.

Sineus said nothing. He drove. The truck rumbled on, a tiny, isolated world of five broken people. Kulagin took a piece of hard, black bread from his pocket. He broke it in two. He offered half to Zoya. She looked at the bread, then at him. She took it without a word and began to eat, her knife resting on her knee.

The truck’s engine sputtered. It coughed once, twice, then died. The sudden silence was absolute. Vast and heavy. They coasted to a stop in the middle of nowhere. A flat, white plain under a sky the color of lead.

Kulagin was the first to speak.

— Fuel’s gone, Commander.

Sineus looked at the gauge. The needle was on empty. He had known this was coming. He had just chosen not to face it. He got out of the truck. The cold hit him like a fist. The air smelled of snow and damp earth. There was nothing in any direction. Just the flat, empty horizon. They were stranded. 150 kilometers was not enough.

— We walk, — he said. It was the only option.

— Walk where? — Morozov asked. His first words in hours. His voice was a dry rasp. — There is nothing.

— We walk east, — Sineus said.

Sokolov had gotten out of the truck. He was looking not at the horizon, but at a map he had taken from his satchel. It was not a military map. It was covered in strange lines and symbols, charts of things that did not appear on any official survey.

— Walking is suicide, — the scientist said. — We will freeze before we cover 20 kilometers.

— Do you have a better idea, Doctor? — Sineus asked. The question was a challenge.

Sokolov did not look up from his map. He traced a line with his finger.

— The main rail line is seven kilometers north of here. According to this, a military transit train—an armored supply run—is scheduled to pass in three hours. It will be moving fast. But it will be heated. And it will be going east.

Sineus looked at him. He was being asked to trust the strange map of a traitor over his own military instincts. To bet their lives on it. It was a test. A shift in power. He had given the order to walk. Sokolov was offering a different path. A harder one. A riskier one. But a better one.

He looked at Kulagin. The Sergeant Major’s face was grim. He shrugged. A soldier’s gesture. It meant: Your call, Commander.

Sineus made the choice. He was no longer just a commander. He was the leader of this broken little unit. And the scientist was no longer just his prisoner. He was his navigator. The choice cost him a piece of his authority, a piece of the certainty that had defined his entire life. He paid it.

— North, then, — Sineus said. His voice was quiet. — We move.

As he turned, he caught his reflection in the truck’s filthy side mirror. It was a dark, distorted shape. For a second, a trick of the light and the grime, he saw Sokolov’s gaunt face shimmering beside his own. A fractured reflection, two men becoming one purpose. He blinked, and it was gone. There was only his own tired face, and the long walk ahead.

The snow began to fall again, thick and wet. The world dissolved into a swirl of white.